This blog has been taken from Moss Side and the Great War Remembered.

It was a 45 minute drive.

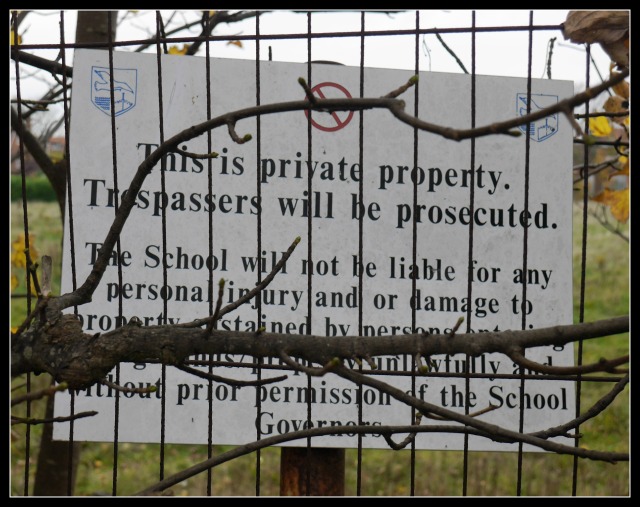

I pulled on wellies, ready to tromp through mud to take a picture. The least I could do, in the circumstances. I could see no obvious entry point so went to the office labelled ‘RSPCA’ – the animal charity that occupies the land – and waited in line to speak to someone. ‘Could you tell me where I get into the field to see the grave?’ I asked. ‘It’s in the far corner,’ he gestured, ‘but you have to make an appointment.’ ‘It didn’t say anything about an appointment online,’ I pleaded with my eyes, ‘I’ve come a long way.’ It didn’t work. ‘Can’t let you in. Health and safety, the ground’s uneven.’ My enthusiasm was rapidly waning as I waited for a contact to call, for next time. Next time? Hah.

My journey to this place had begun when a literary agent (don’t get excited, friend-of-a-friend) sent me a cutting from the Daily Telegraph.

It told of a gravestone, in the corner of that muddy field, protected by Grade II listed building status.

The grave of a horse.

Called Blackie.

Blackie died, aged 37, in this, the former ‘Horse’s Rest’ in Halewood, near Liverpool, in 1942.

It had been an eventful life. Because Blackie was a war horse.

He served throughout the First World War. Saw action at the Somme, Ypres, Arras, Cambrai. And now lies buried near Liverpool, thanks to Lieutenant Leonard Comer Wall. His partner in war. And poet.

Now, I am not one for horses, nor for wars. Have never read, nor seen War Horse.

But it turned out this story had a link even closer to home – and it intrigued me.

Leonard was born ‘over the water’ in West Kirby, in 1896, but his first school, Terra Nova, was a short walk from where I now live, in Birkdale, Southport.

Though the old gate. Requisitioned for war purpose in WWII it later became a school for the deaf. It is now to be turned into a care home after years of planning disputes

A sad sight round the other side. What looks like a World War II air raid shelter is in the foreground

It felt like fate had thrown down a crumb, told me to follow a trail.

Which is why I was there, boots ready for mud, an hour and a half poorer in time, with nothing to show for it. Except a poignant tale, as are so many of that war which failed to end all wars.

Leonard came from a relatively wealthy family, by dint of the Liverpool merchant’s trade. I don’t know when he left Terra Nova, but the little boy next moved some distance away, to Clifton College in Bristol – a short walk from both the places we lived in that city.

More of those crumbs …

When war was declared, Leonard was still at school, but within days had volunteered.

In August 1914 he became a temporary Second Lieutenant in the 1st West Lancashire Brigade, Royal Field Artillery (RFA) but his service began in earnest in 1915.

After action at the Somme and around Arras, came Ypres. Then the Battle of Messines Ridge, in 1917.

Leonard, more than once passed over for promotion, had at last made Lieutenant. Mentioned in dispatches for bravery, he had also penned a poem which, as far as I can see, was his only published work, but enough to gain him entry to the ranks of the War Poets.

RED ROSES

When Princes fought for England’s Crown,

The House that won the most renown,

And struck the sullen Yorkist down,

Was Lancaster.Her blood-red emblem stricken sore,

Yet steeped her pallid foe in gore,

Still stands for England evermore,

And Lancashire.Now England’s blood like water flows,

Full many a lusty German knows,

We win or die – who wear the rose

Of Lancaster.

Leonard Comer Wall

Liverpool Daily Post

13 April 1917

One week after his promotion, on June 7th 1917, the new Lieutenant, riding Blackie, was in action with the 55th (West Lancashire) Division near the village of Wytschaete when he was hit by shrapnel from an exploding shell.

Blackie was wounded and his groom, Driver Francis Wilkinson was killed.

Lieutenant Comer Wall died the next day.

The two men are buried in Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery.

Leonard was twenty years old. An only child. Engaged to be married to Irene Dorothy Bryan (who later, happily, found a new love with whom to share her life).

In his will, Leonard left £180 – quite a sum for a young man – and requested that, should he not survive the war, Blackie be cared for and his medals buried with the horse when he, too, died.

His partner gone, Blackie rode on to the end of the war, wearing his own ‘decorations,’ the scars of his shrapnel wounds.

When the war ended, in keeping with his wishes, Leonard’s mother brought the horse back to its old home of Liverpool, the city from which he had set out four bloody years ago.

There were happy times ahead in his retirement. Blackie, with another war horse, Billie, is said to have led the annual carters’ parade through Liverpool, wearing Comer Wall’s medals, until he was retired to the Horse’s Rest.

There he now lies, presumably with those medals, in a corner of a not-so-foreign field. Unlike poor Leonard.

But the short-lived Lieutenant would, I hope, have been proud to see what happened to his words.

Under an announcement of his death which appeared in a newspaper, ran his line:

‘We win or die who wear the Rose of Lancaster.’

They were brought to the attention of General Jeudwine, the Divisional Commander, who ordered that, henceforward, they should surround the divisional sign, where they were amended to read:

‘They win or die who wear the Rose of Lancaster’

In 1919, the Division chaplain, Canon Coop, had enamelled plaques bearing the motto (known as ‘cocardes’) placed on the graves of the men of the 55th (West Lancashire) Division.

[Picture from Merseyside Roll of Honour]

[Picture from Merseyside Roll of Honour]

Young Leonard’s old school, Clifton College, carved his poet-soldier’s name on the college’s war memorial.

And I’m sure there is understandable pride in the gallantry of its alumni, among them General Haig, Commander of the British Expeditionary Force on the Western Front from late 1915 to the end of the war.

But that pride is far outweighed, for me, by the utter tragedy of the loss, from this one school, of 582 of its boys.

Will we remember them, now 100 years have been and will soon be gone?

I will. With sadness.

And may they rest in peace. Wherever they, their horses and their medals lie.

I drew extensively when writing this on a detailed, well researched and fascinating post by Mike Royden for which I am immensely grateful. It has the pictures I could not provide. If you are at all interested in the military side of the story do read it.

http://www.roydenhistory.co.uk/halewood/warmemorial/wargraves/blackie/blackie_leonard_comer_wall.pdf

Posted on 21 November 2018 under Museum